The first goodbye was at the end of training. I had a good relationship with my host family- they were extremely kind to me and we never had any problems with the exception of the morning of swearing-in when I had a minor disagreement with my host mom over whether or not I would wear a seshoeshoe (traditional dress) for the ceremony. Half-way through training we started cooking for ourselves which meant I spent less time with my family, but there was always some chitchat when I got back from sessions at the end of the day. Nevertheless, I was surprised when, after the ceremony and photos, my host mom started weeping into my shoulder. Touched, I gave her a big hug and promised to visit when I could.

When I got to site, there were four nuns living at the convent where I live: Sisters Giratta, Bridgitta, Alice, and Agatha. When I came back from med-sep, Bridgitta had moved back to the mother house. She was very elderly and they had more comfortable facilities there. I saw her once there while attending the funeral of another nun I did not know. Even though it had been over a year since I had seen her, she greeted me warmly, calling me “Mphonini,” an affectionate nickname for my Sesotho name. Within a month I was back at the mother house attending Sister Bridgitta’s funeral. She had been so kind to me in our limited (by both time and language) acquaintance. I was very sad to see her go.

I said goodbye to my cohort last July. It was tough because I liked those people a lot and I knew it would be a long time until I would see them again. But I was so in love with my job and my life in Lesotho that I didn’t even think of following them back to America.

I had a counterpart that I’ve written about on here before. Her name is Puseletso. We had a great working relationship for most of my first year back after med-sep. Puseletso never explicitly disclosed this to me, but I’m pretty sure she has HIV. One time she showed me her garden in which she was growing a certain kind of spinach she told me she had heard was good for people living with HIV. Another time she told me why she lived alone- she had a husband but he lived in Qacha’s Nek, a distant district, working in a mine. I asked if he visited. She shook her head, looking strangely guilty. “When we are together, we only fight,” she told me. An absentee, abusive, HIV+ mine-worker husband is practically a cliché in Lesotho. These conversations, paired with her frequent illnesses and visits to the hospital in town and the prevalence in Lesotho (23% of adults) lead me to believe that she is HIV-positive. Once or twice she had disappeared for a few weeks, reemerging visibly healthier than I had seen her last, saying that she had been ill but was feeling better and was “ready to work!” So when she disappeared a little over a year ago, I wasn’t too concerned. But then weeks turned to months and she still hadn’t come back. Her phone number was disconnected. I tried not to jump to the worst conclusion, that she had died and no one had told me. Five months later she called me up. She told me she had been ill but was feeling better and was “ready to work!” We met up the next day to make some plans for our projects. She looked like she had aged several years in the time we had been apart. I went into this meeting with caution. Before her absence we had been working toward opening a skills training center, or at least that was our original, stated goal. But as time had gone on, her focus had gotten blurry, saying we needed to start scholarship funds for the OVCs, and that we needed to get donations of toothpaste and lotion for them, and that we could present these donations in a big feast ceremony, like we had done at Christmas. Scholarship funds and donations of toiletries are not bad things, but I had been operating under the understanding that we were working towards the skills training center, which, when up and running, would be financially self-sustaining. Going around to the same businesses, with the same donation request letters, time after time, is not sustainable. This is how most charities in America operate- on donations only. But in Lesotho, charitable giving is not as well established, and, with no tax rebates, not as well-incentivized. PCVs are only supposed to work on projects that have an element of sustainability, and I did not see that in Puseletso’s plans. One of the last times I saw her before her absence I pointed this out to her, explaining that we needed to start an income-generating activity to support the OVCs. She nodded along, but it was in the way Basotho do when they are telling you what you want to hear. So going into our reunion meeting, I decided that if Puseletso wanted to pursue an IGA, I would help her. But if she just wanted my help printing letters and standing behind her as a token white person while she begged shop-owners for donations, I was out. We sat down together and I asked her what she had in mind for the future of CISP. “These OVCs, they are needing scholarships. We must write some letters.” I sighed inwardly. I explained to her that I was not able to help with fundraising efforts for unsustainable donations. She slumped back in her chair. “But you will return to America soon.” In six months, but sure. “When you are in America, you will not forget us,” she said, smiling. I knew what this meant. She was referring to an idea she had floated by me on occasion before, which was that when I went back to America I would fund-raise there on behalf of CISP. I had always gently shot this idea down before, as I have no plans to commit to starting a 501(c)3 for this one-person operation in my village, especially when that one person up and disappears for months at a time with no notice. I deflected by playing dumb. “Of course I will not forget you. I will miss you all very much.” I told her that I was still available to facilitate sessions on business skills, health, and life skills (what I had originally agreed to do with her). She replied vaguely that maybe she would get the OVCs together for a workshop during the upcoming school break. I said I would be happy to help out. But we both knew that this workshop would not materialize. When we said goodbye that day, I knew we were parting ways for good. I was happy to see that she was in good health, but at this point in my service I didn’t have to scrounge for work with people who only saw me as a source of income. Puseletso had moved to a different village when she had gotten out of the hospital, so I knew I likely wouldn’t see her again, expect for maybe passing in town. This has proven true.

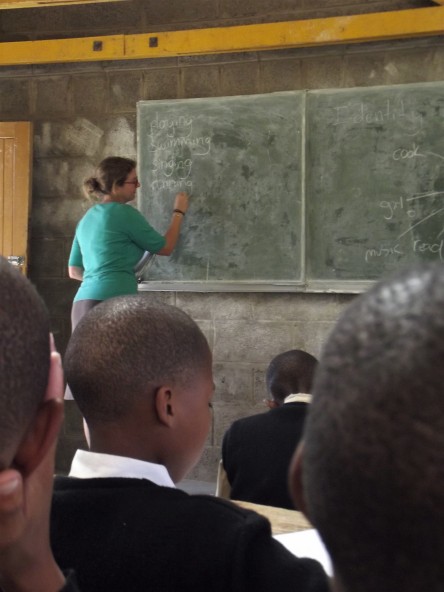

I taught life skills, financial literacy, employability, and sexual and reproductive health to a youth cooperative club at St. Stephen’s High School. St. Stephen’s is a prestigious private school, and you could tell. The students there were smart, focused, and respectful. About eight months after my return from med-sep, the adviser to their club asked me to meet with his students once a week after school. It was my first regular gig as a PCV, and I was over-the-moon to have something fixed on my schedule. A few months later I started coming twice a week so more students could have access to the sessions. Basotho aren’t quite as schedule-obsessed as Americans, so every once in a while I would show up after school and it would turn out the students couldn’t meet with me that day because there was a sports day (field day), trip to Maseru, holiday weekend, etc. This kind of thing happens all the time in Lesotho, so it didn’t faze me much. This April it happened a couple times in a row, then I was away for a week, so almost a month had passed since I had seen the adviser. When I finally tracked him down to ask about the rest of the school year, we looked at the calendar together and realized that I wouldn’t be able to meet with the students again because they were already in exam prep. I blinked. It was the first work thing I had that ended because of my COS, and I hadn’t even realized.

My students at Mohale’s Hoek High School, whom I’ve posted about on here in the past, gave me a goodbye I can only describe as frenetic. I was about five minutes late when I walked into class last Tuesday, and clearly they thought I wasn’t coming because my entrance was greeted with literal shrieks of joyful relief. We did our post-test, then I tried to give them a Dead Poets’-style inspirational speech about their futures without me. No one was paying attention. One of them raised her hand as I looked out at them, exasperated. “Ausi Mpho, we want to play.” Ok, fine. I guess I’m only here to teach them games. Actually, I’m pretty okay with that. We played games for twenty minutes, I led them in a rousing round of kilos, then I started packing my stuff up. “Ausi Mpho, may I hug you?” Haha, sure, I replied. Cue every girl in the class shrieking and mobbing me. It was like they were trying to start a dogpile, but were too short to find the correct pivot point? I had them get in an orderly, single-file line, which they leaped into, jumping and squeaking all the while. Again I foolishly imagined giving warm hugs and meaningful farewells to each student. Again, this did not happen. Each student jumped on me, some hanging on my neck, too busy shrieking and giggling to hear any inspirational words. I laughed and gave in to the chaos.

I had promised my training host family that I would print pictures of us for them, but when I got to the stationary store in Maseru, it was closed. In honor of “African Heroes Day”. Of course. I wasn’t completely empty-handed, though. As always when visiting them, I brought a bucket of KFC, which is something of a delicacy here, and a bag full of clothes I wanted to give to my host sister. People ask me for things all the time here – money, a job, sweets, my banjo, my bicycle, my sunglasses, my phone number. But these people, my host family, had never asked me for anything. Not once. Not every PCV has that experience. They were happy to sing songs and play UNO and scold me for not speaking better Sesotho and ask me about the weather in Mohale’s Hoek as if it was a distant land in another hemisphere. I wasn’t sure how to put my appreciation into words, especially Sestotho words, so I decided to trust it to actions. I colored with my little host sister, promised my other sister I would call from America, and shared a very awkward hug with my host dad (hugs are not common in Lesotho, especially between men and women. I think he was kind of freaked out.). I looked back at the village until the taxi went around a bend in the road.

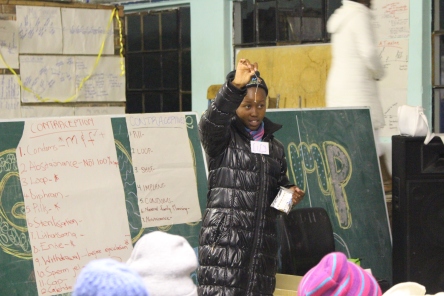

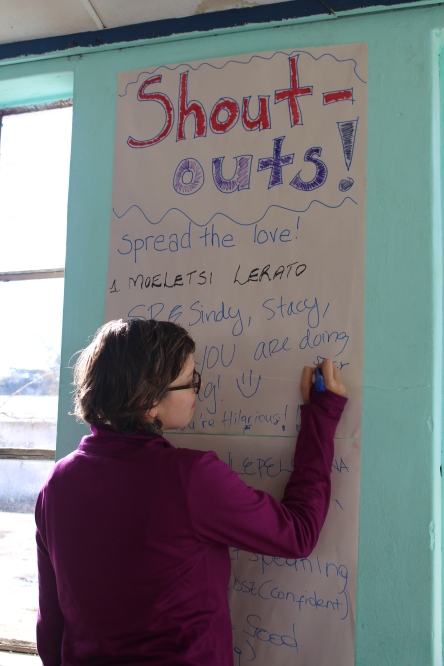

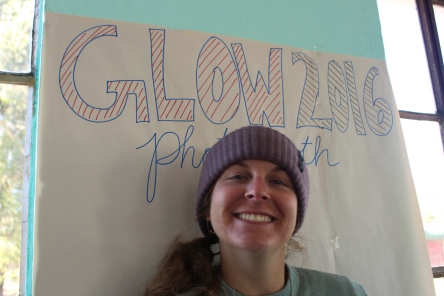

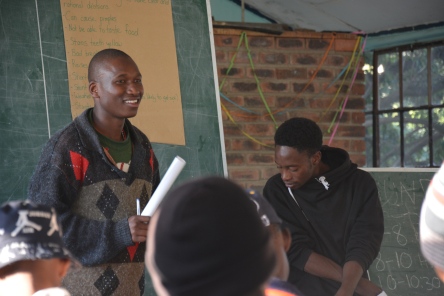

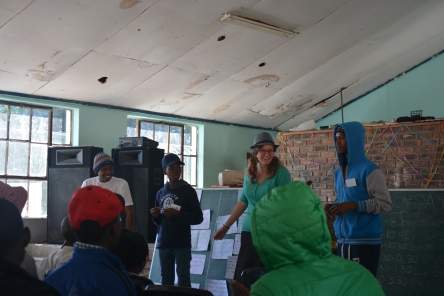

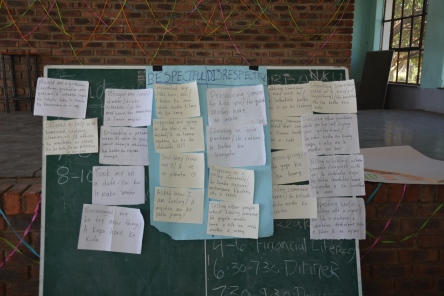

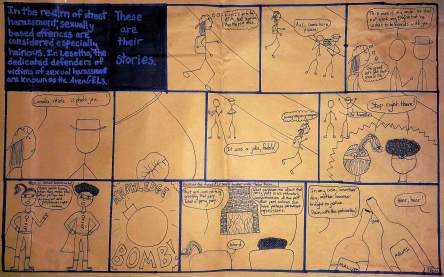

Here are pictures from the BRO (Boys Respecting Others) Camp that we put on at the end of April. It’s the boys’ counterpart to GLOW Camp. 57 campers, 11 advisers, 9 local counselors, 4 days of GTs.

Errbody

Co-direx plus counseling staff

talent show movez

Gumboot dances

Never been able to resist a dance circle

![EMNFUJI-20170103-091425-10[edit1]](https://embrizzle.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/emnfuji-20170103-091425-10edit1.jpg?w=444)

![EMNFUJI-20170103-091639-11[edit1]](https://embrizzle.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/emnfuji-20170103-091639-11edit1.jpg?w=444)